Great Northern Railway

GNR and its workers

For the majority of employees the Works were a way of life as it had for previous generations, an extended family. Skills that were honed by a system of apprenticeships were passed, undiluted to the next generation. The Works fostered a community spirit that survived beyond the life of the Works.

Conditions of apprenticeship

GNR clerkship exam 1917

GNR (I) Works tug-of-war team

GNR (I) Dundalk Works Erecting shop staff

Dundalk Works Erecting shop

GNR Works fire brigade

DEW Government Department letter 1958

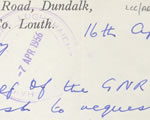

GNR Employees Association letter 1956

In 1919 the Works formed the roots of Dundalk AFC who witnessed one of their proudest moments in April 1942 when they won the FAI cup for the first time. The avant garde of employees became very competitive at quitting time. When the hooter sounded first out of the works, up the slope and onto the Ardee Road would be declared the daily winner. There is no doubt that for the majority of employees the Works was home from home.

That is not to say the relationship between the GNR and its employees was always a happy one, with conflict between stakeholders over issues relating to unions, working hours and pay.

The events of July 1932 are a case in point. Two hundred employees of the GNR were given final notice, and a further 600 were told to work one week in three. All 800 went on strike from 01 August, with the support of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR). The deadlock continued for three weeks until negotiations between the Dundalk Urban District Council (DUDC) and Minister Sean Lemass proved acceptable to both sides.

Standstill

However, with the announcement that station masters and clerical staff wages were to be cut by almost 16 per cent, a further strike commenced on 31 January 1933. The GNR network came to a standstill in the northern half of the country as signal men, porters, drivers and firemen all downed tools. Negotiations eventually settled the strike and workers returned to their stations on 10 April.

Improved economic conditions at the end of the 1930s gave GNR a reprieve from its precarious financial position. Then with the outbreak of World War II, fuel rationing and grounding of many motor vehicles meant that rail transport became central for economic survival. Moreover Dundalk became a black market capital as smuggling was prevalent. By 1943 the total staff employed by the company numbered 6,888. Following the conclusion of World War II and the Emergency the newly formed Labour Court awarded an increase of 2/10 per hour. This led to jubilant scenes at the Works with one delighted blacksmith declaring "I got more than I expected"1 . By 1948 however, the long term future of the company looked pessimistic. Labour costs had increased by 142% in less than a decade. With the financial resources of the company almost at an end both governments were forced to intervene. Despite this, the operating losses continued to soar. By 1955 the GNRB was losing £1 million a year. With the closure of unprofitable lines now widespread a meeting was organised by the Dundalk Chamber of Commerce to voice their concerns on the bleak outlook for the local economy. In 1956 total losses summed almost £1.2 million. Such figures could not of course be sustained. Each employee received notice of the closure of the GNR Locomotive Works in January 1958, resulting in the loss of some 1000 jobs. The Irish government helped to establish Dundalk Engineering Works and other companies were also set up, including Frank Bosner & Co. and Heinkel Cabin Scooters Ltd.

Footnotes:

1. McQuillan, Jack "The Railway Town" page 141

Next page - Industry and Commerce » «Previous page - Engineering Pride

- home |

- about project |

- online catalogue |

- online exhibitions |

- activities |

- oral history collection

- about us |

- contact us |

- legal |

- acknowledgements

© Cross Border Archives Project . Website design and development by morsolutions.

This project is part financed by the European Union through the Interreg IIIA Programme managed for the Special EU Programmes Body by the East Border Region Interreg IIIA Partnership.